Elektrooniline muusika mõjub kehale oma korduvuses kui kosmos, kus aeg ja ruum sulavad kokku ning loovad keskkonna, kus saab tantsida lõputult. Reivikultuuri juured peituvad 1980ndate lõpus ja 1990ndate alguses, mil subkultuur kasvas põrandaalustes klubides ning lokaalides. Praeguseks on sellest kujunenud üks megamaailm ja popkultuurinähtus, mille toel on arenenud ning populaarsust kogunud erinevad muusikafestivalid, kvaliteetne helitehnika, VJ-mine, mood ning ilmselgelt ka tantsukultuur. Selle kõige maagilise kõrval on algusest peale pead tõstnud ka enesepõletamine. Nähtub, et tundide viisi enese transsi tantsimisel on nüüdistantsuga ideoloogiliselt nii mõnigi seos ning nõnda kolib antud subkultuur aina enam teatrilavale. Kas liikumine on ka vastupidine: nüüdistants siseneb klubikultuuri? Millised on nähtuse kasvuraskused? Kuidas publik selle vastu võtab? Jne… Nendele küsimustele otsisime vastuseid koos koreograafi Üüve-Lydia Toomperega, kelle praktikas on peol kui sotsiaalsel kontekstil oluline koht.

Kui Üüve-Lydia seitse aastat tagasi Berliini kolis, tundis ta teatavat surutust nende tantsude ees, mis oli Eestis seadnud ja lavastanud. Tal oli kindel soov leida keskkond, kus inimesed sooviksid liikuda oma vabast tahtest ilma, et keegi neid selleks sunniks või kohustaks. Ta valis selleks sotsiaalseks kontekstiks klubikultuuri, loomulikult aitas sellele kaasa Berliini peokultuuri mastaapsus ja omanäoline stiil, mida selles linnas kohtab. “Kõik tantsivad, aga kõik ka räägivad tantsimisest. Peo loomulik osa on tantsust rääkimine,” avab Toompere elektroonilise muusika klubide tausta.

Oma olemuselt on klubikultuur vägagi teatraalne ja performatiivne, need tegevused, mis käivad peo juurde, on justkui stseenid ühest suuremast esinemisest. Olgu selleks siis peoks valmistumine, kostüümi valimine, klubiruumi ja vabastava atmosfääri loomine valguse, heli- ja videoprojektsiooni kaudu, teemapidude korraldamine või enese vaba väljendamine tantsupõrandal. Vast kõige olulisem ühisosa peo- ja teatrikultuuri vahel on publiku kohalolu. Mõlemas kontekstis on neid vaja olukorra aktiveerimiseks, kuigi seda erinevas rollis: kui teatris on eelkõige (kuigi see on muutumises) tarvis vaatajat, kes laval toimuvat vastu võtaks, siis klubikultuuris on vaja kogejat, kes oleks valmis loodud ruumiga kaasa tulema. Mulle tundub, et kaasaegsetes etenduskunstides oodatakse publikult aina enam just klubikultuuris levinud aktiivsust ja avatud meelt.

Üüve-Lydia on viimasel ajal palju klubides esinenud ning tunnistab, et see situatsioon erineb teatrisüsteemist nii mõnelgi moel. “Peol esinemine jääb alati peol esinemiseks: inimesed ei ole tõenäoliselt tulnud eesmärgiga näha ainult sinu esinemist, nad küll vaatavad ja toetavad sind, aga sa ei ole olulisem kui pidu ise.” Oma hiljutistest kogemustest toob Toompere näiteks esinemise puuris, mis asetses klubis DJ set’i vahetus läheduses, seal tajus ta end osana peost. Kui esineda aga klubis, kus on interjööris lavapiir selgemalt välja joonistunud ning kus on levinud ka teised etendusvormid, nagu dragshow’d ja vogue ball’id, kehtestab etendussituatsioon end teisiti ning publik jääb etteastet n-ö rohkem vaatama.Publik üldiselt toetab klubides esinejaid ja on huvitunud sellest, mis toimub, kuid klubisituatsioon erineb oluliselt teatrisituatsioonist, kus publik pühendab oma tähelepanu ja aja kunstniku tehtud tööle.Seetõttu on etendaja klubis pigem peo osa kui nähtus omaette, mis asjast asja teeb, nagu see on teatris.

Peosituatsioon on tõepoolest loomulik keskkond, kus inimesed on valmis vabalt liikuma ja lahti ütlema oma valehäbist. Selle pinnalt on Üüve-Lydia loonud töötubade seeria “Techno Praxis”, mille tööreeglid on ta üles korjanud klubi Berghaini tantsupõrandalt. Juhiseid on kolm ja need on lihtsad:

- Ruumi sisenedes tuleb mõni aeg tantsida iseendaga (huvitav, juba sellesse kirjeldusse on sisse kodeeritud teatud sotsiaalsus, tantsitakse just iseendaga mitte üksi).

- Kui tantsupõrandal kohtuvad kellegagi pilgud ning tekib kontakt, siis sellel oleks hea lasta kesta, isegi kui olukord on asjaosalistele ebamugav. “Lasta sellel kesta ja venitada seda kummi pikemaks ning vaadata, kas see situatsioon võib hoopis naljakaks muutuda.” Selle sees on märgata, kui loomulik on meie kehakeelele hakata teist, keda jälgime, alateadlikult oma liikumises jäljendama.

- Kui üksi tantsimine on end ammendanud, siis tasub minna kellegi juurde, kelle liikumine sümpatiseerib, ning üritada teda kopeerida.

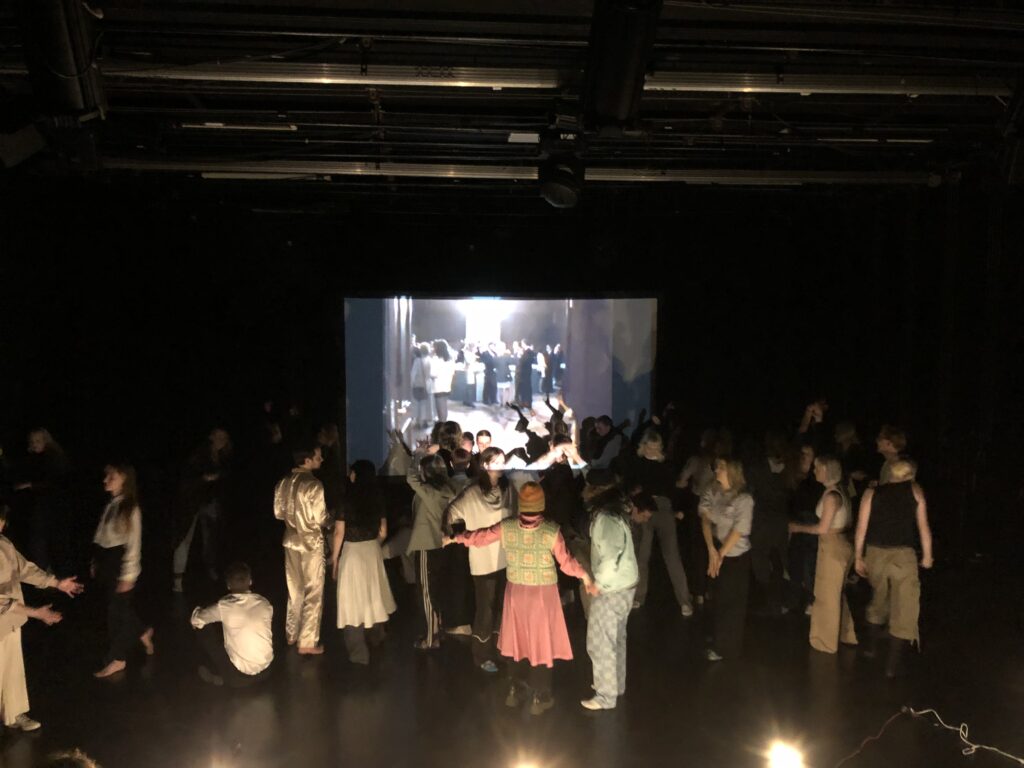

Toompere sõnutsi oleneb väga, kus töötuba teha. Berliinis näiteks ei ole mõtet sellega töötada, sest see on juba sealne reaalsus ning peosimulaatori läbimine ei julgusta inimesi avanema, nagu see juhtub Eestis. Kuigi otseselt ei ole vahet, mida ja kuidas töötoa sees tantsitakse, on Üüve-Lydia aeg-ajalt tunnetanud, et kui ei keskenduta tema suunistele, siis ei ole võimalik ka kohale jõuda – kui jääda lõputult ainult iseendaga tantsima, siis tegelikult võib lihtsalt peole minna ja töötoa vahele jätta. Teine huvitav nähtus on põrandal aelemine, mis on end põrandatehnikana nüüdistantsus kehtestanud, kuid klubikultuuris kleepuval põrandal mitte. Üüve-Lydia sõnutsi läheb Sõltumatu Tantsu Lava töötubades asi tihti liiga kaasaegseks tantsuks kätte ära – tundub, et kontekst (teatrilava), kus töötuba läbi viiakse, hakkab dikteerima ka workshop’i sisulist kulgu. Olles “Techno Praxis’ega” töötanud erinevates kontekstides, saab nentida, et võib-olla rohkem kui ruumgi, mõjutab kohtumise kulgu osalejate grupp. Üüve-Lydia jaoks kõige parem töötuba on seni olnud KUMUs (Jeremy Shaw näituse “Phase Shifting Index” raames), kus suur osa osalejatest ei olnud mitte tantsijad, vaid elektroonilise muusika festivalide külastajad ning olid kohale tulnud sõprusgruppidena. Töötoa olemust kujundavad selles osalejad, esialgu hakkab domineerima nende oma isiklik taust, edaspidi aga teistega kontaktis olles leitu. Hea on nentida, et küsimus “Kas ma teen praegu õigesti?” on “Techno Praxis’es” kadunud.

Nüüdistantsus seevastu on mul tunne, et oleme veel üsna kaugel sellest õige ja vale ära kaotamisest. Isegi kui seda välja ei hääldata, siis suhtumisest on ikkagi võimalik tajuda, et mingid asjad on rohkem aktsepteeritud kui teised. Teatrisaali tuleb publik ka teise ootusega – mida mulle siis pakutakse? Töötuppa minnakse aga avatumalt ja pigem sooviga midagi kogeda. Ükskõik, mis lavale pannakse ja teatrisituatsiooni tõstetakse, kehtestab end etendusena ning seal hakkab kohe tööle teatri märgisüsteem. Teosele pühendumisega kaasneb huvitav tendents, kus tundub, et publik unustab end natuke ära. Oma heaolu antakse täiesti kunstniku kätte, mis ühelt poolt on väga ilus ja habras hetk, teistpidi aga vastutus, milleks kunstnikul alati ei ole soovi ega vastutusvalmidust. Miks unustame teatrisaalis ära, et meil säilib publikuna autonoomsus oma valikute üle samamoodi nagu klubis?

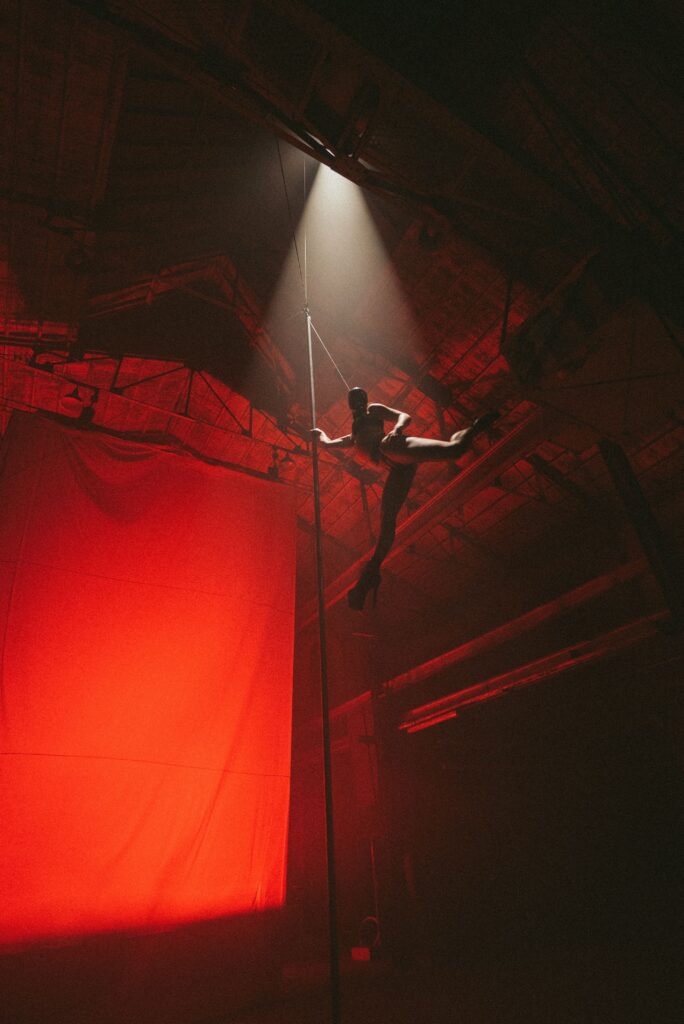

Instagramist alguse saanud Üüve-Lydia alter ego Fluxxious on omanäoline nähtus meie kultuuriruumis. Tema sotsiaalmeediavoog on täis sensuaalse alatooniga postitantsust erinevate thrist-trap’ideni (ahvatluslõksudeni). Tema välimus nihestub vastavalt kontekstile, see võib varieeruda alastusest lateksis kuni küllalt konservatiivse maskini. Oma olemuselt on ta poliitiline tegelane, kes teeb ja postitab, mis tahab, ja käitub oma kehaga nii, nagu talle õige tundub. Teatrilavale ei ole ta veel kuigi palju jõudnud, eelkõige ongi ta esinenud klubides, kus ta töötab funktsionaalselt seal pakutavate vahenditega nagu puur või post. Sellises kontekstis Toompere teadliku nihestamisega (mis kaasaegsetes etenduskunstides on väga levinud) ei tegele, sest too lähenemine on eelkõige oskuspõhine, nt postitants. Esiteks ei ole klubikultuuris aega proovi teha ning teiseks ei oota sealne publik eksperimenteerimist, pigem siiski meelelahutust.

Kui olukord keerata aga teistpidi – klubikultuur tuua teatrilavale, siis tuleb nihestamine kindlasti mängu. Fluxxious on esinenud ka galeriiruumis ning seal laseb ta lahti kindlast vahendist ning liigubki pigem reaalsuse nihestamise suunas, nt fetišite kaudu, mida üritab alati keerata seksuaalsusest ära mängulisuse suunda. “Mulle meeldib mõelda, et nii muutub asi intelligentsemaks.” Kui subkultuuri lavale toomist mitte nihestada, võib see muutuda vaid esteetikaks, mis omakorda suhtub originaalkonteksti ehk liiga üleolevalt, kui mitte öelda vägivaldselt. Ükski subkultuur ei ole vaid esteetika, nii ka elektrooniline muusika ja reiv, nende taga on oma struktuur, kontekst ja süsteem.

In the same rhythm until the end of the party, or even better, until the next one

Electronic music in its repetitiveness acts as an embodied galaxy, where the time and space merge into one and create an environment in which one could dance endlessly. The roots of rave culture can be traced back to the late 1980s and early 1990s, as the subculture evolved in underground clubs and venues. By now rave has become a type of megaworld and pop culture phenomenon, which has influenced the growing popularity of various music festivals, the development of high-quality sound technology, VJ-ing, fashion trends and obviously dance culture. There seem to be ideological links between dancing yourself into trance in rave clubs and contemporary dance performances, thus the subculture is moving onto the theatrical stage. Is this tendency reciprocal: is contemporary dance also intertwining with the club culture? What challenges does this phenomenon face? How does the audience respond to it? Etc… To seek out answers to these questions, I had a discussion with choreographer Üüve-Lydia Toompere, whose practice in large part focuses on party culture as a social context.

Seven years ago Üüve-Lydia moved to Berlin and at the time she felt a certain dissatisfaction regarding the dances she had created and directed in Estonia. She had a clear ambition of finding an environment, where people would have a natural urge to move without anyone forcing or obliging them. Toompere encountered it in Berlin’s unique and vast party culture, hence she took it up as a social context for further research. ‘Everyone is dancing there, and everyone is also talking about dance – it is a natural part of the party,’ Toompere discloses the background of electronic music clubs.

In its nature, club culture is a highly theatrical and performative setting– the activities that go hand in hand with a party act as scenes from a larger performance. Whether it be getting ready to go out, choosing an outfit, creating a liberating atmosphere in a club with lights, sound and video projections, organising theme parties, or expressing oneself freely on the dance floor. Perhaps the most significant link between party- and theatre cultures is the presence of an audience. In both contexts, the audience is needed in order for the situation to be activated, although from different perspectives. If in theatre an audience member is primarily (though this is changing) a spectator who observes artist’s work, then in a club environment they are rather a participant who is willing to explore the space that an artist has created. It seems to me that in contemporary performing arts the artists are expecting the audience to be as open-minded and free-willing as it is common in nightclubs.

Üüve-Lydia has recently been performing in clubs and acknowledges that the circumstances differ in several ways from how it usually is in theatre. ‘Performance at a party will always remain a performance at a party: probably people have not come with the goal of seeing you perform. Eventhough they watch and support you, you are not more important than the party itself.’ From her recent experiences Toompere recalls a performance inside of a cage, that was located near the DJ set – there she felt as if she was a part of the party. However, when performing in a club in which the border between stage and hall is more distinct, both in the interior design as well as the fact that other performances such as drag shows and vogue balls are held there, then the audience also tends to view the performance as more of a theatre piece. Although the audience is supportive towards performers in clubs, they are mainly seen as a part of the party, rather than an independent spectacle as is the case in theatre space.

The party situation is indeed a natural environment in which people are ready to let go of their inhibitions and move freely. Based on the guidelines Üüve-Lydia picked up from Berghain’s dance floor, she created a series of workshops called ‘Techno Praxis’. There are three main instructions, and they are quite simple:

- Upon entering the space, one is encouraged to dance with themselves for a while (Notice, how this description already encodes a certain social aspect – as one is guided to dance with themselves rather than by themselves).

- When one makes eye contact with someone on the dance floor, it is good to let the connection linger for some time. Even if the situation is uncomfortable for the parties involved. ‘Stretch that rubber longer and see if the situation can turn into something funny’. Within this, it is noticeable how natural it is for our body language to subconsciously imitate the movements of the person we are observing.

- If dancing with oneself becomes tiring, one could approach someone else, whose movement they find appealing and try to imitate them. Eventually a large group of dancers may form, based on imitating each other’s moves.

Toompere explains that the location of the workshop influences the final outcome significantly. For example, there is no reason to work with this content in Berlin, as the party culture is already a big part of the local reality, and going through a party-simulator does not encourage people to open up, as it does in Estonia. Although it does not really matter how one dances in the workshop, Üüve-Lydia has occasionally felt that if the participants do not focus on her instructions, it is not possible to reach the desired result. If one only keeps dancing with themselves indefinitely, then they might as well just go to the party and skip the workshop. Another interesting aspect is the use of floor, which as floorwork is an important part of contemporary dance but is not commonly seen on the sticky nightclub floors. According to Üüve-Lydia, the workshops at Sõltumatu Tants Lava often turn too contemporary-dance oriented; it seems that the context (the theatre stage) where the workshop is held, begins to dictate the content of it as well. Having worked with ‘Techno Praxis’ in different contexts, it can be concluded that the group of participants and their background influences the course just as much as the space. However it is nice to discern that the question of ‘Am I doing it right?’ is not present in ‘Techno Praxis’.

Contrariwise I feel that in contemporary dance we are still quite far from getting rid of the concepts of right and wrong. Even if it is not explicitly stated so, you can still sense from the attitude of the audience that certain approaches and artistic choices are more accepted than others. The audience enters a theatre with an expectation – ‘What will I be offered/shown?’. In contrast, when people go to a workshop, they are more open and inclined to experience something. Regardless of what is presented on stage, it immediately establishes itself as a performance, and the theatre’s semiotics come into play. With the audience’s decision to dedicate themselves to the performance, there is an interesting tendency where it seems like they forget about themselves a little. They place their experience and well-being entirely in the hands of the artist, which, on one hand, is a beautiful and fragile moment, but on the other it is a responsibility that not all artists are willing or ready to take on. Why do we as audience members forget that we retain the autonomy of our choices in theatre just as much as we do in clubs?

Originating from Instagram, Üüve-Lydia’s alter ego Fluxxious is a unique phenomenon in our cultural space. Her social media feed is filled with sensuous undertones, from pole dancing to various thirst-traps. The character’s appearance shifts according to the context she appears in, ranging from nudity in latex to a relatively conservative mask. By nature, she is a political figure who does and posts what she wants and treats her body as she sees fit. Fluxxious has not yet made her debut on the theatre stage. She primarily has performed in clubs, where she works functionally with the available tools, such as a pole or a cage. In a nightclub context Toompere does not consciously work with dis-location/placement (which is very common in contemporary performing arts), because this approach is essentially skill-based, like pole dancing. Because firstly, there is no time for rehearsals, and secondly, the audience there does not expect any experimentation rather some entertainment.

However, when we flip the situation around and choose to put aspects of club culture onto the theatre stage the dislocation becomes a significant tool. Fluxxious has also performed in gallery spaces, and there she is not tied to certain objects anymore as she is in clubs. In galleries she has worked with dislocating the fetishes, always trying to steer them away from the initial sexual associations towards playfulness. ‘I like to think that the stage context makes things more intelligent.’ If the subculture brought to the stage is not dislocated at all, it may appear as mere aesthetics, which, in turn, might regard the original context condescendingly, if not even violently. No subculture is just aesthetics; the electronic music and rave scene have their own structure, context and system. And should be respected as such.